Plastic Law

Introduction

ELAW is pleased to present this overview of laws designed to tackle the growing problem of disposable plastic. This site currently focuses on laws applied from the design of the plastic product to final disposal. We also share summaries of select laws and decisions from courts addressing the problem. For the most part, we focus on laws from outside the U.S. and Europe.

Recognizing the serious environmental, health and economic impacts associated with plastic, governments around the world are enacting laws and policies to address plastic, especially single-use plastic. Manufacture and use of plastic around the world is growing. National Geographic shares eye-opening statistics including:

“About 8 percent of the world’s oil production is used to make plastic and power the manufacturing of it. That figure is projected to rise to 20 percent by 2050.” i

“Nearly a million plastic beverage bottles are sold every minute.” ii

But one statistic stands out as a problem that can be addressed swiftly:

“40 percent of plastic produced is packaging, used just once and then discarded.” iii

Governments are adopting an array of measures that take aim at single-use plastic manufacture, trade, use, and waste. Because product packaging is a major driver of plastic use, some lawmakers are focusing on ways to transform consumer product distribution that eliminates single-use packaging altogether.

Civil society players are urging their governments to adopt effective laws targeting the rampant production and overuse of single-use plastic. ELAW provides this resource to share strategies and encourage robust action to reduce single-use plastic and transform consumer product delivery systems worldwide.

False Solutions

It is important that efforts to tackle single-use plastic do not encourage other unsustainable practices, sometimes referred to as “false solutions.”

For decades, plastic manufacturers have touted recycling as the solution to plastic waste, but it turns out that less than 10% of the world’s plastic is recycled. iv In fact, industry leaders never expected recycling to be the answer, even while promoting it. Describing investigations into the plastic industry and its advocacy of recycling as a solution to accumulating plastic waste, a writer for FRONTLINE reports:

“Facing heightened public concern about ever-increasing amounts of garbage, the image of plastics was falling dramatically. State and local officials across the [U.S.] were considering banning some kinds of plastics in an effort to reduce waste and pollution.

But the industry had a plan; a way to fend off plastic bans and keep its sales growing.

It would publicly promote recycling as the solution to the waste crisis — despite internal industry doubts, from almost the beginning, that widespread plastic recycling could ever be economically viable.”v

Currently, incineration (including waste-to-energy facilities), bioplastics, compostable plastics, down-cycling (recycling higher grade plastics into things such as clothing and roads), chemical recycling, and other strategies are touted as solutions to the growing plastic problem. None of these strategies alone or in combination with others is safe, feasible, or effective to address the sheer volume of single-use plastic that is being generated.

“Companies like ExxonMobil, Shell, and Saudi Aramco are ramping up output of plastic — which is made from oil and gas, and their byproducts — to hedge against the possibility that a serious global response to climate change might reduce demand for their fuels.”vi These companies are going to continue promoting false solutions to ensure governments don’t curb the manufacture and use of plastic – and so people continue to grab a plastic straw to go with their to-go beverage in a plastic cup.

Well-designed laws will address unsustainable alternatives directly. Laws that specifically ban biodegradable plastic as part of bans on single use plastic can be found in Jamaica, the Bahamas, and New Zealand, among others.

Jamaica’s ban on biodegradable plastic is part of its

single use plastic law, which prohibits the import or distribution of single use plastic in commercial quantities, and includes degradable, biodegradable, oxo-degradable, photo degradable or compostable plastic bags. The Bahamian plastic law likewise includes biodegradable plastic bags in its prohibition on single use plastic bags. The British territory of Turks and Caicos Islands also includes biodegradable plastics in its prohibition on single use plastics. Similarly, in New Zealand's plastic law an explanatory note clarifies that the definition of “plastic bags” includes bags that are compostable or biodegradable, and as of 2022 New Zealand has also adopted regulations that will ban bio-based plastic drink stirrers, plastic cotton buds, and plastics that contain pro-degradants.

A few good resources describing false solutions include:

- Greenpeace, Throwing Away the Future: How Companies Still Have It Wrong on Plastic Pollution “Solutions” (2019).

- The Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA) has published a technical report, Chemical Recycling: Status, Sustainability, and Environmental Impacts vii, and a briefing document viii that explain why “chemical recycling” or “advanced recycling” are false solutions. ix

- UNEP’s 2015 report: Biodegradable Plastics and Marine Litter. Misconceptions, concerns and impacts on marine environments.

- Changing Markets Foundation, Talking Trash: the corporate playbook of false solutions to the plastic crisis (September 2020)

Laws Requiring Less Toxics in Plastic

In addition to banning problematic plastic products, it is helpful when a law promotes better alternatives. Laws supporting better product design are showing up in several places. The best examples are those implementing new delivery systems so that reusable products replace single-use.

For example, the city of Berkeley in California requires truly compostable packaging for take-out food and reusable containers for eat-in establishments. Rather than focus exclusively on single-use plastic, this ordinance addresses disposable packaging more broadly.

In Bangladesh, the government requires the use of jute bags for bulk commodities listed in the Mandatory Jute Packaging Act, 2010, such as rice, sugar, and fertilizer. The law has twice been expanded to encompass more products and requires jute packaging for preservation and transportation of 20 kg or more of 17 commodities throughout Bangladesh. The law not only reduces plastic waste, but supports Bangladesh’s jute industry.

While not going as far as replacing plastic with sustainable alternatives, some laws encourage companies to manufacture less-toxic plastic and plastic that is more likely to be recycled. For example, Zimbabwe encourages “the design of plastics containing few pollutants, are recyclable and durable when put to their intended use.” Plastic Packaging and Plastic Bottles Regulation S.I. 98, 2010, Art. 4.

Bans on Single-Use Plastic

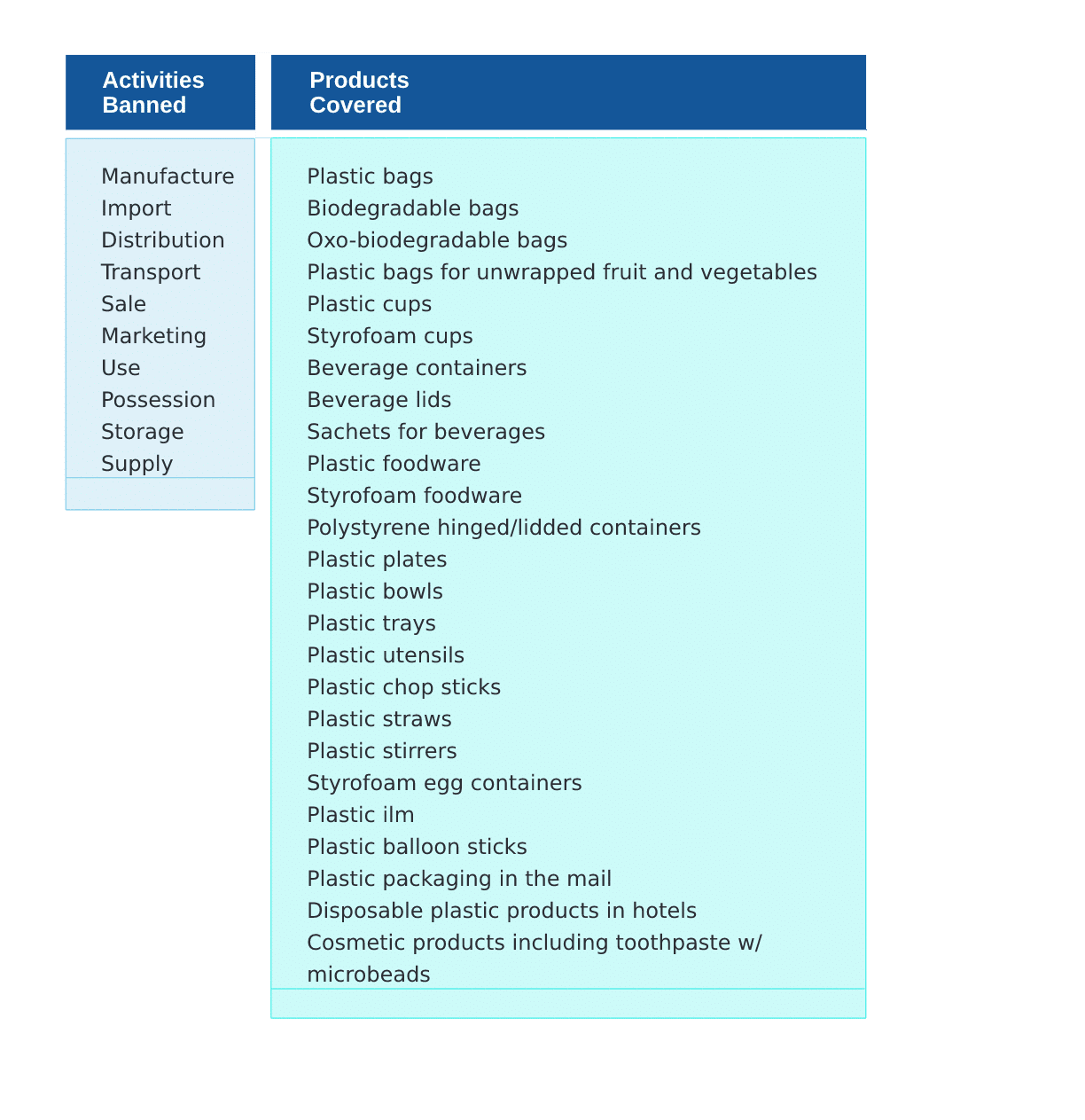

Years ago, governments started banning the distribution of plastic bags, and then added other single-use plastic items such as straws, takeaway food packaging, and utensils. In response to the ubiquity of plastic in everyday life, single-use plastic bans have dramatically grown in numbers and in scope, as shown below.

In ELAW’s review of laws from around the world, we have found more than 35 jurisdictions that ban manufacture of at least some plastic products, and similar numbers (with significant overlap) of jurisdictions banning import. Laws banning the manufacture and import of single-use plastic products may be the most effective way to reduce consumption and disposal.

To be effective, bans must be easily enforced. For example, banned items should be clearly defined and easy to identify. Some bans on plastic bags describe a specific thickness measured in microns which can be difficult for an inspector to identify. If plastic thickness is used, one helpful measure is to require plastic thickness to be stamped on the bags. Banning distribution of all plastic carry bags is an even better way to make a ban clearly enforceable.

Some laws limit the distributors that are covered, which can make a ban harder to enforce. For example, Taiwan’s 2019 law applies to department stores in shopping centers but not to chain convenience stores and fast food facilities found in the same shopping centers. See, Environmental Protection Administration, Executive Yuan Huan-Shu-Fei-Tzu No. 1080056916 (8 August 2019).

Finally, many otherwise strong bans are weakened by inclusion of a long list of exemptions. For example, Antigua and Barbuda bans import, distribution, sale and use of polyethylene or petroleum-based shopping bags, but includes a long list of bags exempt from the ban and allows the Minister responsible for Trade, Commerce & Industry, Sports, Culture and National Festivals to exempt other bags.

Single-use plastic bans present an opportunity to encourage related reforms that address waste management problems and encourage more sustainable products.

For more information, see False Solutions and Supporting Better Product Design and Promoting More Sustainable Alternatives.

Bans on Import/Export of Waste

Separate from addressing the manufacture and use of the products themselves, some countries are banning the import and export of plastic waste. For example, Senegal bans the import of plastic waste and the export of waste unless the importing country allows the import and has adequate treatment facilities. Senegal, Loi n° 2020-04 (8 January 2020), Arts. 19-20.

Taxes and Fees on Single-Use Products

Closely related to bans are taxes/levies/fees on plastic bags and other single-use plastic products. Some laws implement a mixed approach, banning some items and taxing others in an effort to discourage their use. This approach can help ensure that banned items are not simply replaced by other disposable items. For example, a 2003 South African law bans bags less than 24 microns thick and taxes thicker bags, which encourages use of reusable carry bags.

Most examples of single-use plastic taxes and fees are imposed on consumers. However, these fiscal measures can be imposed at other points of the production chain to promote more sustainable products and better reflect external costs of plastic production and use. For example, Algeria imposes a Value Added Tax (VAT) on plastic bags imported and produced locally.

Deposit-Refund Systems (DRS)

Deposit-refund systems (DRS) (also known as deposit-refund schemes or bottle bills) have a long history of improving collection of refillable and recyclable containers. These programs generally require the consumer to pay a small deposit at purchase that is refunded when the container is returned to the retailer or to a collection center. These laws most commonly apply to beverage containers, but could easily be expanded to cover other plastic products as well.

Whether a DRS is the right program in a jurisdiction will depend on factors including whether there are people dependent on collecting and selling these items who would be displaced by a more formal system.

Some DRS laws are designed to put the costs of the program on producers (including importers and distributors). DRS can be one element of an Extended Producer Responsibility scheme.

DRS laws are found in many regions of the world, including Australia, Barbados, Fiji, Senegal, and Tanzania.

Extended Producer Responsibility

Recently, many governments, civil society, and others are promoting Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) as a strategy to reduce the growing menace of plastic.x

While some advocates applaud EPR as a way to ensure producers take responsibility for reclaiming and reducing waste, others see it as another way to continue unsustainable disposable use practices. EPR programs need to be well designed to ensure good outcomes.

Thomas Lindqvist is credited with developing the concept of EPR in 1990. More recently, Lindqvist defined EPR as:

[A] policy principle to promote total life cycle environmental improvements of product systems by extending the responsibilities of the manufacturer of the product to various parts of the entire life cycle of the product, and especially to the take-back, recycling and final disposal of the product. xi

Lindqvist hypothesizes that EPR programs are popular across jurisdictions because they help tackle the waste problem while putting the cost of the program on the manufacturers and distributors, rather than on governments and taxpayers.xii Strong EPR programs shift responsibility of implementing the program (such as collecting used plastic products), and/or financing the program, on those responsible for putting the product in the market. In principle, this should lead producers to adopt more sustainable production models, designs and materials.

EPR does not refer to one specific program. Instead, it describes a principle that guides a set of instruments adopted to help improve products and product delivery systems to reduce associated environmental, social, and health impacts. Lindqvist explains that EPR is implemented through a mix of “administrative, economic, and informative policy instruments.”xiii

In Europe, EPR has gained a specific meaning and there are some well-developed EPR programs in place.xiv However, in other places, EPR may look different.

The general concept of EPR programs is that brand owners/producers become responsible for covering the full environmental and social costs associated with their products. In the realm of plastics, EPR is generally aimed at requiring producers or brand owners to pay the cost of recovering the plastic packaging from their products (or the plastic product itself) and managing the recovered plastic in the most environmentally-sustainable method possible which may include reuse, repair, or recycling. Effective EPR programs avoid final disposal (landfilling or incineration) to the greatest extent possible. If designed well, EPR programs encourage manufacturers and distributors of products to reduce packaging or improve packaging design to limit waste. In addition, EPR can reduce the need for virgin resources, by increasing reuse of material.

While a robust EPR program might be the end goal, a step-wise approach to implementation using simpler programs may be appropriate. For example, a jurisdiction could require companies distributing beverage containers to reclaim the containers and pay the cost of preparing them for reuse, mechanically recycling them, or, as a last resort, properly disposing of them. Where community members already informally collect these containers to sell, a new program should include and fund those already doing the work. Such a program could include fees to cover education programs or other steps toward a holistic approach to reduce plastic waste.

A jurisdiction seeking to launch a successful EPR program must have related programs in place, or commit to developing them on a parallel track. For example, an existing recycling program can help other EPR programs succeed.

Jurisdictions that do not have a recycling market or other prerequisites for a comprehensive EPR program might adopt elements that can stand alone such as:

- Programs that encourage or require replacing disposable plastic products with reusable and refillable alternatives.

- Programs requiring distributors and retailers to take back the packaging from products they sell.

For example, the Returnable Containers law in Barbados requires any entity that sells beverages (for use off-site) in containers covered by the Act, to accept any qualifying empty container and provide the refund value. Id. at sec. 4(1). In turn, distributors must accept qualifying beverage containers of brands they distribute from retailers and refund the value of each container. Id. at sec. 4(2). If beverage containers returned to the distributor are unusable or not reused, they must be disposed of in accordance with applicable waste laws. Id. at sec. 6(1).

The Returnable Containers law is an example of an EPR program, because it requires distributors to take back the plastic bottles they sell. The law in Barbados is coupled with a ban on import, distribution, sale and use of single use plastic containers (other than those identified in the Returnable Containers law), cutlery, straws, and plastic bags made with petroleum-based resin. Control of Disposable Plastics Act, 2019.

Simple requirements could make businesses responsible for collecting other material as well.

Preliminary Design Questions

To be successful, an EPR program must be designed to operate in the local context where it will be implemented. EPR systems should be created through a transparent, participatory process led by the government that brings in all stakeholders. Such a process would create opportunities for many views, including people working informally in the waste sector and those creating new businesses that reduce the use of single-use products and delivery systems.

In designing a program, two big questions must be addressed first, and there are divergent opinions, with no consensus about which answers lead to the strongest EPR programs with regard to these two issues:

- Products Covered

Which products to include in an EPR program is a critical first question. There are at least three points-of-view:

• Some advocates promote inclusion of all materials (from highly recyclable to non-recyclable) to ensure producers are responsible for the environmental impacts of their entire range of products. (Advocates for such broad programs usually also promote a system under which producers only pay for materials management – they do not directly manage the materials themselves.)

• Others argue that highly recyclable materials should not be part of EPR programs so that EPR does not compete with any existing recycling programs or displace people who earn money by collecting and selling these materials.

• Finally, others prefer that EPR systems only address non-recyclable and toxic products. These are the products that put the most strain on local communities and they are the products that most need to become more environmentally friendly.

- Role of the Producer

The second big question is whether the EPR program should be “operational” (meaning that the producers themselves run the program) or “financial” (meaning that the producers pay the local government or others to run the program).

The choice depends on many factors, including whether there is rigorous government oversight and safeguards against corruption. Financial programs preserve flexibility to accommodate informal and community-based recycling collection programs and other initiatives that support the local economy.

Overall Program Design

With these points highlighted, we can add more generally that an effective EPR program should include the following characteristics or components:

- Reduces not only plastic pollution, but total environmental harm (including greenhouse gas emissions and toxic emissions).

- Shifts the financial burden shifted to the producer.

- Structures fees to incentivize producers to implement the waste hierarchy in packaging design and improve sustainability (“eco-modulated fees”). Fees would be lower when packaging is reduced, or higher if the packaging includes certain chemicals. This framework can be augmented through the adoption of penalties and bonuses. For example, a financial bonus for using standardized reusable packaging, or a penalty charge for using a single-use container where a reusable alternative is readily available.

- Builds on existing waste management systems. If waste is managed at the municipal level, the EPR program should be compatible with existing municipal systems.

- Is carried out uniformly across the jurisdiction with equal access to the program in rural and urban areas.

- Includes measurable and verifiable targets for reduced packaging, landfilling, and increased reuse and recycling. This requires baseline data to be available or generated. Performance targets could be specific to types of plastic packaging.

- Defines products covered clearly.

Compliance and Enforcement

- Mandatory compliance with legally binding requirements and serious penalties for violations. Programs initiated on a voluntary basis by individual companies are unlikely to meet many public policy goals.

- Strong enforcement provisions, including the ability of citizens and NGOs to enforce the law.

- Reporting of detailed and verifiable data (including data on downstream management) that is publicly available and disclosed quickly enough to allow real-time monitoring of the system.

- If the EPR program is operated by an industry-created entity, there must be strong oversight with third-party monitoring for compliance.

Incorporating Local Workers and Businesses

- Designed to incorporate existing local workers and businesses already playing a role in reducing waste, recovering materials, repairing and recycling.

Informal Recyclers/Wastepickers

- Include waste pickers in the design of new legislation. Traditionally, informal recyclers, waste pickers and their organizations have not been included in discussions leading to EPR legislation.

- Ensure that the EPR system will be remunerative for the informal sector.

- Clearly define the legal rights of waste pickers (e.g., waste picking is not theft). Be aware that laws can both recognize and restrict waste pickers activities, creating practical barriers to their activities.

- Attention must be focused on guaranteeing that the law or regulations allow informal waste pickers to work without complicated regulatory oversight or administrative burdens. Some laws establish a registry or certification process for waste pickers before they can participate in waste management activities and/or access benefits and rights. If a law includes this requirement, it is important to include safeguards to make this process easily accessible. and requirements for agencies and/or other stakeholders to promote waste pickers registration.

- In some jurisdictions, laws recognizing and formalizing waste picking are vague and cannot be implemented until regulations are adopted. These regulations may never materialize, which prevents waste pickers from pursuing their work and enforcing their rights.

- EPR laws should include measures to promote inclusion, and address capacity building and broader livelihood issues affecting waste pickers, such as child labor.

- Some countries, have broader policies addressing waste pickers. For example, Brazilian national waste management laws, policies and strategies include several provisions promoting inclusion and recognition of waste pickers. Starting at the highest level, a National Policy of Solid Waste objective is to incorporate waste pickers in waste management actions (Law 12.305 National Policy of Solid Waste, article 7). This policy requires municipalities to include programs and actions for the participation of cooperatives and other forms of waste picker organizations in their waste management plans (Article 19). Regulations implementing Law 12.305 include several provisions promoting the participation of waste pickers, including a requirement to create working conditions and social and economic inclusion opportunities improvement programs (Article 43). The regulations also state that waste collection systems will give priority to the participation of cooperative and other forms of organizations of waste pickers (Article 40). Additionally, Brazil also developed a “Pro Waste pickers Program” to coordinate federal government actions to support and promote the work of waste pickers and the improvement of their working conditions.

- Laws should allow/encourage waste pickers to participate in public bidding for different waste management activities, especially activities they are already carrying out and have experience with.

- In some countries, waste pickers and informal recyclers have gained further recognition over their work including preference over different waste management (recollection and treatment) activities, through litigation and law reform.

Treatment of the Product

- Priorities should be consistent with the waste management hierarchy, starting with avoided waste, reduced packaging, reduced single-use plastic packaging, reusing, repairing, and finally mechanically recycling.

- A ban on incineration xv (with or without energy recovery) and plastic-to-fuel operations (including thermal or chemical) as a final disposal method. In some instances, an incineration ban may already be in place through a different law.

- The treatment methods for material recovery include reuse and mechanical recycling. Any approaches to turn collected waste into fuels are considered waste incineration and should be banned.

Other Program Elements

- Education program designed and implemented by government agencies or third-parties not associated with promoting plastic production or use.

- Costs of the program are differentiated among products to take into account the impact of the product on the environment and communities, rewarding producers for more sustainable or least harmful products.

- Producers bear the full cost of the program. Full cost includes at least collection, transport, treatment, public education, data collection and sharing, administration, and any needed clean up.

Education

Finally, none of these programs targeting single-use plastic will be successful without education. Some laws

require education to help raise public awareness of the need to reduce use of plastic.

Several organizations have developed and compiled helpful educational resources, including the following:

- The Plastic Pollution Coalition, General resources for all grades

About this project

Governments are addressing the problem of plastic differently. Therefore, this resource is not limited to single-use plastic law bans or regulations. We include relevant provisions whether they come from stand-alone laws, environmental codes, health codes, waste management laws, or customs laws. Currently, this resource focuses on laws applied from the design of the plastic product to final disposal.

Research for this project focused outside the U.S. and Europe.

ELAW U.S. appreciates information generously shared with us by public interest lawyers around the world who make up the ELAW Network, as well as information, advice and review of the section on EPR by: Mao Da, China ZW Alliance; Xavier Sun, Taiwan ZW Coalition; Dharmesh Shah; Beth Grimberg, Polis; Sarah Doll, Safer States; Julliet Phillips, Environmental Investigation Agency; Delphine Levi Alvares and Larissa Copello, Zero Waste Europe; Taylor Cass Talbott, WIEGO; and Neil Tangri and Monica Wilson, Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA). Special thanks to Cecilia Allen and Doun Moon at GAIA.

Endnotes

Si National Geographic, Fast Facts about Plastic Pollution, by Laura Parker (20 December 2018), https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2018/05/plastics-facts-infographics-ocean-pollution/ (citing World Economic Forum).

ii National Geographic, Fast Facts about Plastic Pollution, by Laura Parker (20 December 2018), https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2018/05/plastics-facts-infographics-ocean-pollution/ (citing Euromonitor International and Container Recycling Institute).

iii National Geographic, Fast Facts about Plastic Pollution, by Laura Parker (20 December 2018), https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2018/05/plastics-facts-infographics-ocean-pollution/ (citing Roland Geyer, University of California, Santa Barbara).

iv National Geographic, Here’s How Much Plastic Trash is Littering the Earth, by Laura Parker (20 December 2018) (citing Great Britain’s Royal Statistical Society data), https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2017/07/plastic-produced-recycling-waste-ocean-trash-debris-environment/ See also, United Nations Environment Programme, Our Planet is Drowning in Plastic Pollution.

v Plastics Industry Insiders Reveal the Truth About Recycling, Patrice Taddonio (31 March 2020) https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/plastics-industry-insiders-reveal-the-truth-about-recycling/; see also Plastic Wars, FRONTLINE, Season 2020, Episode 14 (31 March 2020), https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/film/plastic-wars/

vi The Plastics Pipeline: A Surge of New Production Is on the Way, by Beth Gardiner (19 December 2019), posted on the website of the Yale School for the Environment at https://e360.yale.edu/features/the-plastics-pipeline-a-surge-of-new-production-is-on-the-way

vii Rollinson, A., Oladejo, J. (2020). Chemical Recycling: Status, Sustainability, and Environmental Impacts. Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives. doi:10.46556/ONLS4535.

viii Chemical Recycling: Distraction, Not Solution, a briefing that pulls from the technical report “Chemical Recycling: Status, Sustainability, and Environmental Impacts” (see previous footnote). GAIA also explains “chemical recycling” and “advanced recycling” and why these are false solutions in a blog: https://www.no-burn.org/crblog/.

ix Chemical Recycling: Distraction, Not Solution, webinar (June, 2020).

x Note that EPR programs address producers’ responsibility for other products too. Here we focus on EPR programs to address plastic packaging and products.

xi Lindhquist, T (2000). Extended Producer Responsibility in Cleaner Production: Policy Principle to Promote Environmental Improvements of Product Systems (2000). IIIEE, Lund University, at p. v.

xii Lindhquist, T (2000). Extended Producer Responsibility in Cleaner Production: Policy Principle to Promote Environmental Improvements of Product Systems (2000). IIIEE, Lund University, at p. vi.

xiii Lindhquist, T (2000). Extended Producer Responsibility in Cleaner Production: Policy Principle to Promote Environmental Improvements of Product Systems (2000). IIIEE, Lund University, at p. v.

xiv See, Institute for European Environmental Policy, EPR in the EU Plastics Strategy and the Circular Economy: A focus on plastic packaging, 9 November 2017 (revised 19 December 2017) (available at: https://ieep.eu/uploads/articles/attachments/9665f5ea-4f6d-43d4-8193-454e1ce8ddfe/EPR%20and%20plastics%20report%20IEEP%2019%20Dec%202017%20final%20rev.pdf?v=63680919827)

xv Incineration with or without energy recovery and plastic-to-fuel operations (including thermal or chemical).

ELAW partnered with Plastic Pollution Coalition, Break Free From Plastic Europe, and The Surfrider Foundation U.S. to build the Global Plastic Laws Database. It is the most comprehensive tool to date to research plastic legislation that has been adopted around the world. The Database tracks legislation across the full life cycle of plastics and organizes policies according to life cycle categories and key topics.